1-7Dattakala Institute of Pharmaceutical Science and Research, Solapur- Pune Highway,

Swami-Chincholi (Bhigwan), Pune, MH- 413130

8Dattakala College of Pharmacy, Solapur- Pune Highway,

Swami-Chincholi (Bhigwan), Pune, MH- 413130

Corresponding author Komal Bhagwan Meher

Article Publishing History

Received:

Accepted After Revision:

Pharmaceutical formulations and are therefore an essential part of a pharmaceutical formulation. Their flexibility, having so many chemical structures, physical characteristics, and behaviors, permits tight control of drug release profiles, greater stability, and even better bioavailability. The review has successfully presented the centrality of pharmaceutical science to governments, mainly because of the use of polymers. We consider how polymers are classified on the basis of their source (natural, synthetic, or semisynthetic) and then the role that they play in a formulation, either as binders, disintegrants, coating agents, or matrix formers. We explore the use of polymers in the development of advanced delivery systems such as controlled-release matrices, nanoparticles, micelles, and hydrogels (purposefully designed to avoid obstacles posed by the physiology and deliver targets).

Particular focus is on so-called smart or stimuli-sensitive polymers, which can undergo a property change in response to an environmental stimulus such as pH, temperature, or a particular enzyme, resulting in site-specific release of a drug. This abstract relies on the critical analysis of the underlying postulates and modern contributions to polymer-based drug delivery and thus emphasizes the revolution brought to the development of more effective, safer, and patient-friendly therapeutic alternatives through polymer science.

Polymers, Pharmaceutical Formulations, Synthetic & Natural Polymers.

Meher K.B, Davare K.D, Patil V.P, Pati D.C, Punekar P.D, Babu D.C, Babar V.B, Aleesha S.K. A Review on Polymers Used in Pharmaceutical Formulations. International Journal of Biomedical Research Science (IJBRS). 2026;02(1)

Meher K.B, Davare K.D, Patil V.P, Pati D.C, Punekar P.D, Babu D.C, Babar V.B, Aleesha S.K. A Review on Polymers Used in Pharmaceutical Formulations. International Journal of Biomedical Research Science (IJBRS). 2026;02(1). Available from: <a href=”https://shorturl.at/e7ajO“>https://shorturl.at/e7ajO</a>

INTRODUCTION

In contemporary pharmaceutical science, the polymers are fundamental ingredients that are indispensible, extending far beyond the more mundane use as inert excipients to form the core of sophisticated drug delivery systems [1,2]. The functionality of such big molecules is carefully designed into formulations so as to regulate release characteristics, stabilize the formulation and curtail the bioavailability of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [2,3]. Polymers can also be used to modulate the pathway of a drug through the human body to produce a controlled-release dosage form that maintains steady therapeutic levels and thus has reduced the number of doses required and the dose-limiting side effects [3-5]. The use of polymers can be attributed to the capacity to regulate drug release through possible processes such as diffusion, erosion and swelling [5].

Not only does the category of natural polymers such as cellulose and starch adapted as a binder and disintegrant, semisynthetic polymers such as hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) in sustained-release matrices and advanced synthetic polymers such as poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) in biodegradable implants determine the release pattern of the drug and the therapeutic performance of the drug, but also forms the basis of a huge industry in the pharmaceutical industry [6-10]. New evolutions in polymeric materials, such as the creation of smart polymers that react to certain physiological stimuli, are bringing a new generation of highly-targeted and personalized therapies, and polymers are at the core of the future of pharmaceutical formulation [10].

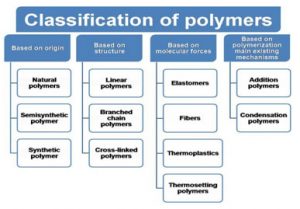

Classification of Polymers: Polymers [11-13] can have different chemical structures, physical properties, mechanical behavior, thermal characteristics and can be classified in different ways by following below are,

Figure 1: Classification of Polymers

- Based on Origin

1.Natural Polymers: Natural polymers are those which are derived from either plants or animals. We refer to them as animal and plant polymer.

Examples : Cellulose, Jute, Silk, Wool, RNA, DNA, Natural rubber

2.Semisynthetic Polymers: Semisynthetic fibres are created from natural fibres that have been chemically treated to improve specific physical traits, such as tensile strength and lustre.

Examples include Cupra, ammonium silk, and viscose rayon.

3.Synthetic Polymers: Synthetic fibres are manufactured in laboratories through the polymerisation of fundamental chemical components [13 & 14].

Examples include nylon, Orlon, polystyrene, PVC, and Teflon.

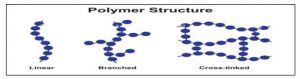

Based on structure

Linear polymers: In these polymer, monomers are interconnected to form an elongated, linear structure. These chains do not possess any additional branches or side chains.

Examples: Polyester, Polyethene

Branched Polymers: The straight long chain of molecules is accompanied by various side chain. Due to there irregular packing these molecules exhibit low density, tensile strength and melting point [14].

Examples: Polypropylene, Amylopectin, Glycogen

Crosslinked Polymers: The monomeric units are interconnected to form a three-dimensional framework in which cross link play a crucial role. These cross link contribute to the hardness, rigidity and brittleness of the network structure.

Examples: Bakelite, Formaldehyde resin, Vulcanized rubber

Figure 2: Structure of Polymers

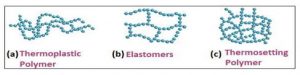

- Based on molecular forces

- Elastomer

These polymers are characterized by polymer chains being held together by the weakest attractive force. They consist of randomly coiled molecular chains with minimal cross links. When a strain is applied, the polymer stretches and upon release of the force, it return to its original position. Such polymers exhibit elasticity and are commonly referred to as elastomers [15].

Examples : Silicone, Natural rubber

Fibers: They possess a strong intermolecular attractive force similar to hydrogen bonding. Additionally, they exhibitremarkable tensile strength making them highly valuable in the textile industries.

Examples: Nylon-66, Terlyene

Thermoplastic Polymers: Polymers with intermolecular force between elastomer and fibers can be easily shaped by heating and then cooling at room temperature. These polymers may have a linear or branched chain structure.

Examples: Acrylic, Polypropylene

Thermosetting Polymer: This polymer exhibit high hardness and remain non melting when exposed to heat. They do not soften when subjected to pressure and cannot be reshaped. Due to their cross-linked structure these polymers are not recyclable.

Examples: Melamine,Silicone,Polyurea

Figure 3: Structure of Polymers based on molecular forces

Based on Polymerization Addition Polymer

Addition Polymer: Addition polymers are formed by repeatedly adding monomers without removing any byproducts. As a result these polymers consist of all the atom from the monomers making them a multiple of the monomer unit [15-19].

Examples: Orion, Teflon

There are two types of addition polymer:

Homopolymer: The formation of addition polymers due to the polymerization of single polymeric species is called homopolymer.

Copolymer: The formation of addition polymer which occur due to addition polymerization from two different monomer is called a copolymer.

Condensation Polymer: The formation of these compounds occur through the combination of two monomers resulting in the elimination of small molecules such as water, alcohol, or ammonia. Ester and amide linkage are present in their molecular mass does not correspond to an integral multiple of monomer units [9].

Examples: Polyamide, Polyurethane

Characteristics of an ideal polymer:

- It should be inert and compatible with the terrain.

- It should be non- poisonous and physiologically inert.

- It should be fluently administrable.

- It should be easy to fabricate and must be affordable.

- It should have good mechanical strength.

- It must have comity with utmost of the medicines.

- It mustn’t negatively affect the rate of release of the medicine.

- It mustn’t have tendency to retain in towel and must be a good biodegradable material.

- It should be inert and compatible with the terrain.

- It should be non- poisonous and physiologically inert.

- It should be fluently administrable.

- It should be easy to fabricate and must be affordable.

- It should have good mechanical strength.

- It must have comity with utmost of the medicines.

- It mustn’t negatively affect the rate of release of the medicine.

- It mustn’t have tendency to retain in towel and must be a good biodegradable material.

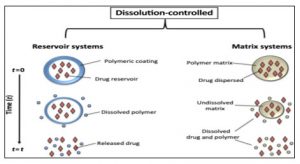

Dissolution controlled release: Controlled-release drug formulations can be created by reducing their dissolution rate. Strategies to achieve this include the development of suitable salts or derivatives, coating the drug with a slowly dissolving substance, or embedding it within a tablet that contains a slowly dissolving carrier. Various methods can be utilized to create dissolution-controlled systems: One approach involves layering the drug with rate-controlling coatings, allowing for pulsed delivery. If the outermost layer is a rapidly dissolving bolus of the drug, it can quickly establish initial drug levels in the body, followed by subsequent pulsed intervals.

Another alternative is to deliver the drug in the form of beads, each featuring coatings of varying thicknesses. Due to the different coating thicknesses, the release of the drug will occur progressively. Beads with thinner coatings will supply the initial dose, while those with thicker coatings will maintain drug levels later on. This principle underpins spansule technology or microencapsulation. The dissolution rate at a steady state is represented by the Noyes-Whitney equation: dC/DA (C-C) dt h, where dC/dt indicates the rate of dissolution, D represents the drug’s diffusion coefficient through the pores, h denotes the thickness of the diffusion layer, A is the surface area of the exposed solid, C is the saturated solubility of the drug. Depending on their technical complexity, these systems can be classified into two categories: A. Matrix type B. Encapsulation type [13-18].

A.Matrix dissolution: Matrix dissolution devices are created by compressing the medication with a slowly dissolving carrier to form a tablet. The controlled release is achieved by: 1. Modifying the tablet’s porosity 2. Reducing its wettability 3. Allowing it to dissolve at a slower pace. The rate of drug release depends on the dissolution of the polymer. Examples include Dimetane Extencaps and Dimetapp Extentabs.

Encapsulation dissolution/reservoir dissolution-controlled system: The microencapsulation method involves coating or enclosing drug particles. These pellets are placed inside hard gelatin capsules, commonly referred to as ‘spansules’. Once the coating material dissolves, the entire drug contained within the microcapsule becomes readily available for dissolution and absorption. In this case, the drug release is influenced by both the dissolution rate and the thickness of the polymer membrane, which can vary from 1 to 200 μ. The rate at which the coat dissolves is affected by the stability and thickness of that coating. Examples include: 1. Ornade spansules. 2. Chlorpheniramine repetabs [11-15].

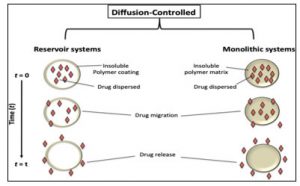

Figure 4: Dissolution model for the Reservoir & Matrix systems for Encapsulation

Diffusion controlled release: Diffusion systems are defined by the fact that the rate at which a drug is released depends on its movement through an inert membrane barrier, typically made of an insoluble polymer. Generally, two categories of diffusional systems are identified: reservoir devices and matrix devices. In reservoir devices, the drug release adheres to Fick’s first law of diffusion. Here, D represents the diffusion coefficient of the drug within the polymer, J denotes the flux (amount per area per time), and dc/dx indicates the change in concentration concerning polymer distance [10-13].

These systems can be classified into two categories: A.Reservior Devices , B.Matrix Devices

Reservoir Device: Reservoir devices consist of a drug core, known as the reservoir, which is encased in a polymeric membrane. The characteristics of the membrane influence how quickly the drug is released from the system. One of the benefits of reservoir diffusional systems is that they can achieve zero-order delivery, and the release rate can be adjusted depending on the type of polymer used. However, reservoir diffusional systems have drawbacks, including the need for the system to be physically implanted at the site, challenges in delivering high-molecular-weight substances, and the risk of dangerous dose dumping if the system ruptures [7-9].

B. Matrix Devices/ Monolithic system : A matrix device is made up of a drug that is uniformly distributed within a polymer matrix. In this model, the drug located in the outer layer, which is in contact with the bathing solution, dissolves first and then diffuses out of the matrix. This process continues as the boundary between the bathing solution and the solid drug shifts inward. Clearly, for this system to be governed by diffusion, the dissolution rate of the drug particles within the matrix must significantly exceed the rate at which the dissolved drug diffuses out of the matrix.

Figure 5: Dissolution model for the Reservoir & Matrix systems for Monolithic system

Combination of Dissolution and Diffusion release systems: These systems can integrate both the diffusion and dissolution of the drug and the matrix material. The drug can diffuse from the dosage form similar to some previously described matrix systems, while the matrix simultaneously undergoes a dissolution process. The complexity arises from the fact that as the polymer dissolves, the path length for the drug’s diffusion may change. This typically results in a moving boundary diffusion scenario. Zero-order release can occur only when surface erosion takes place and the surface area remains constant over time. A key benefit of such a system is that the bioerodible nature of the matrix prevents the formation of a ghost matrix, thus eliminating the need for removal from implant sites. However, the drawbacks of this system include the challenges in controlling release kinetics due to multiple release processes and the potential toxicity of the degraded polymer must be taken into account. Another approach to creating a bioerodible system is by chemically bonding the drug directly to the polymer.

Typically, the drug is released from the polymer through hydrolysis or enzymatic reactions. A third type, which employs a combination of diffusion and dissolution, is the swelling-controlled matrix. In this case, the drug is dissolved within the polymer; however, instead of an insoluble or eroding polymer as seen in prior systems, the polymer swells. This swelling allows water to penetrate, leading to drug dissolution and diffusion from the swollen matrix. In these systems, the rate of release is strongly influenced by the polymer’s swelling rate, the drug’s solubility, and the proportion of the soluble fraction within the matrix. This system often minimizes burst effects since polymer swelling must first occur before drug release [11-18].

Osmotic controlled release: In these systems, osmotic pressure acts as the driving force for the controlled release of medication. Imagine a semi-permeable membrane that allows water to pass through but blocks drug molecules. A tablet with a drug core encased by such a membrane, when immersed in water or any bodily fluid, will draw water into the tablet due to the difference in osmotic pressure. These systems usually come in two distinct configurations. The first type features the drug in a solid core along with an electrolyte, which dissolves upon water interaction. The electrolyte creates a significant osmotic pressure difference. The second configuration contains the drug in a solution inside an impermeable membrane within the device, while the electrolyte is situated around the bag.

Both types have one or more holes drilled through the membrane that permit drug release. In the first scenario, the high osmotic pressure is alleviated by forcing a solution containing the drug out through the opening. Likewise, in the second scenario, the elevated osmotic pressure compresses the inner membrane, causing the drug to be expelled through the hole. The benefits of osmotically controlled devices include the ability to achieve zero-order release. There is no need for reformulation for various drugs, and drug release is not affected by the surrounding environment of the system. However, the drawbacks of these systems are that they can be significantly more costly than traditional alternatives, and the quality control measures required are more extensive compared to standard tablets [5-15].

Ion exchange system:-Ion-exchange systems typically utilize resins made of cross-linked, water-insoluble polymers. These polymers feature functional groups that form salts, positioned at regular intervals along the polymer chain. The drug is attached to the resin and is released through an exchange with ions in the vicinity of the ion-exchange sites. The process can be represented as Resin Drug + X → Resin-X + Drug, and conversely, Resin Drug + Y → Resin-Y + Drug, where X and Y are ions found in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The released drug then diffuses out from the resin. The drug-resin complex is formed by combining the resin with the drug solution, either through repeated exposure of the resin to the drug in a chromatography column or through extended contact in a solution.

The timing of drug release from the resin is determined by factors such as the diffusion area, length of the diffusion path, and the rigidity of the resin, which relates to the amount of cross-linking agent used during resin production. This system is particularly beneficial for drugs that are prone to degradation due to enzymes, as it provides a protective mechanism by temporarily altering the substrate. However, this controlled release method has the drawback that the release rate depends on the concentration of ions in the administration area. While the ionic concentration in the GI tract generally remains fairly stable, variations in diet, fluid intake, and individual intestinal content can influence the rate at which the drug is released. One enhancement to this system is the application of a hydrophobic rate-limiting polymer, like ethyl cellulose or waxes, as a coating for the ion-exchange resin. These systems depend on the polymer coating to regulate the rate of drug release [3-14].

Application of polymers used in pharmaceutical formulation: Polymers are play a vital role in pharmaceutical formulations given as follows:

Tablets: Tablets are the most prevalent form of dosage for medications intended for oral administration. The drug’s release from the tablet can be regulated by modifying the formulation’s design and components. In tablet formulations, polymers serve as disintegrants and binders. For example, disintegrants include starch, cellulose, alginates, polyvinylpyrrolidine, and sodium CMC.

Binders made from polymers consist of glucose, starch, HPMC, gelatin, alginic acid, polyvinylpyrrolidine, sucrose, and ethyl cellulose. Additionally, polymers can be used to conceal a drug’s unpleasant taste and to provide enteric coating for tablets, such as shellac and zein. Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) improves the compressibility of tablets [2-10].

Capsules: Capsules are typically made from gelatin. There are two types of gelatin: hard gelatin and soft gelatin, each with a different composition. Fillers like microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) and starches are utilized to occupy space within the capsule. To address the issue of aggregation, various polymers such as starch and sodium starch glycolate are combined with the capsule material [2-13].

Polymers in gels: Gel systems are comprised of either physical or chemical cross-links that limit the movement of interconnected polymer chains. Gels exhibit unique rheological characteristics. Cross-linked gels are often referred to as hydrogels. These materials are also classified as smart polymers because they exhibit varying gelling behaviors depending on the water environment. The most frequently utilized hydrogels include poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate), poly(methacrylic acid), and poly(acrylamide). In the pharmaceutical sector, cross-linked gels are mainly employed for localized drug delivery to the skin, oral cavity, vagina, and rectum [7-19].

Swelling controlled release systems: In numerous drug delivery systems, the size of the dosage form can change during the drug release process due to the swelling of the polymer matrix. While the primary mechanism for drug release is diffusion, examples of systems that demonstrate swelling-controlled release include physically and chemically crosslinked gels. For controlled drug release, chemically crosslinked hydrogels, such as poly(hydroxyethylmethacrylate), have been utilized to facilitate controlled drug release from medical devices, whereas physically crosslinked hydrogels that rely on swelling can be easily produced by directly compressing a drug with a hydrophilic polymer, such as HPMC [8-16].

Temperature-responsive drug release: Numerous studies have been conducted on the design and use of controlled systems for drug delivery that utilize temperature as an external trigger. The polymers employed to achieve such release characteristics are known as thermoresponsive polymeric systems. Typically, homopolymers and copolymers of N-substituted acrylic and methacrylate amides (for example, poly(isopropyl acrylamide)) are used for these applications. More specifically, there are two categories of thermoresponsive polymer systems: those that demonstrate a positive temperature response and those that exhibit a negative temperature response. Polymers in the first category show an upper critical solution temperature, below which the polymer contracts as the temperature decreases. In contrast, negative temperature-dependent polymers possess a lower critical solution temperature and will shrink when the temperature rises above this threshold [6-14].

Polymers in parenteral: We have various kinds of polymers, such as methacrylic acid and its alkyl amide derivative. Methacrylic acid functions as an interferon inducer, which is effective in treating cancer-related illnesses, while its alkyl amide variant serves as a plasma expander, increasing plasma levels in the human body. For instance, insulin injections are utilized in diabetes management, and multiple polymer types are employed in their formulation, acting as reservoirs that bond with insulin and release it at the intended site [4-11].

Ocular drug delivery systems: Enhancing the ocular contact duration of solutions involves adding polymers to an aqueous medium such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), methylcellulose, carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), and hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC). The increased viscosity of the solution helps to minimize its drainage. By elevating the viscosity of a pilocarpine solution from 1 to 100 cps through the addition of methylcellulose, the rate constant for solution drainage was decreased by a factor of ten, while the concentration of pilocarpine in the aqueous humor only increased twofold.

Ocusert consists of a drug reservoir, which is a thin disk made of a pilocarpine-alginate complex, situated between two clear discs of microporous membrane created from ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer. These microporous membranes allow tear fluid to flow into the drug reservoir, facilitating the dissolution of pilocarpine molecules, which are then released at a steady rate of 20 or 40 mg/hr for a duration ranging from one hour to seven days [2-9].

Application in cosmetics: The treatments for hair and skin that are revealed include a novel quaternary chitosan derivative. These derivatives serve as effective agents, especially for keratin in hair, as well as for enhancing and conditioning hair. Several products are available on the market, such as oxidation hair coloring formulas, hair toning products, skin creams, hair setting lotions, hair treatment solutions, and gels.

Nanoparticles and microparticles: Polymeric nanoparticles and microparticles are utilized for drug encapsulation, offering protection against degradation, regulated release, and targeted delivery. These particles can be engineered to respond to specific physiological conditions, such as changes in pH or temperature, releasing the drug only under predefined circumstances. PLGA nanoparticles are widely researched for delivering anticancer drugs and vaccines, safeguarding the encapsulated drug from degradation and facilitating controlled release. They can also be modified with targeting ligands for precise drug delivery.

Like nanoparticles, polymeric microparticles are employed for drug encapsulation and regulated release and are frequently utilized in depot formulations to ensure sustained drug release over longer durations. The creation of advanced medication delivery systems that enhance patient adherence and treatment effectiveness is significantly reliant on polymers. Targeted delivery systems direct medications to specific tissues or cells, while controlled-release formulations extend the therapeutic effect’s duration. Polymeric microparticles and nanoparticles provide protection, regulated release, and targeted administration while adapting to physiological conditions to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes. Their functionality and versatility make them a vital component of modern medication delivery systems [3-15].

Water-soluble polymers: New applications for water-soluble synthetic polymers span a wide array, including scientific initiatives like drug delivery systems and tissue engineering scaffolds, as well as environmental efforts such as removing heavy metals. Fields focused on information generation also explore fresh opportunities for these materials, such as in electrically responsive or optical films. Water-soluble synthetic polymers have been engineered with properties previously only seen in natural polymers to meet the demands of these innovative applications. The introduction of reactive functional groups is not the only method to address specific challenges. This structural versatility places water-soluble polymers in a pivotal role within the realms of nanotechnology and smart materials.

This brief overview highlights the most recent advancements in the applications of water-soluble synthetic polymers, particularly concentrating on polyethylene glycol, polyvinyl alcohol, polyacrylamide, polyvinylpyrrolidone, and poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide). Through this summary, the intelligent features and sensitive structural control accessible to this class of materials via manipulation of strong hydrophilic interactions will be clarified. Polyethylene glycol, commonly referred to as PEG or polyethylene oxide (PEO) based on its molecular weight, is a typical water-soluble polymer. It has been utilized in a variety of applications, including lubricating coatings, osmotic pressure agents, electrolyte solvents, cosmetic ingredients, and medical laxatives. Recent advancements in nanoscience and technology, as well as in environmental engineering, have opened new opportunities for these polymers and are propelling the development of innovative properties [2-8].

Types of Polymers in Pharmaceutical Drug Delivery

Polymers in floating drug delivery system: Polymers play a vital role in floating drug delivery systems, helping ensure that medications reach specific areas of the gastrointestinal tract, particularly the stomach. Researchers have been exploring natural polymers for their effectiveness in targeting drug delivery to the stomach. Some notable examples include chitosan, pectin, xanthan gum, guar gum, gellan gum, karaya gum, psyllium husk, starch, and alginates [3-9].

Polymers in Mucoadhesive Drug Delivery Systems: The latest advancements in mucoadhesive polymers are making waves in drug delivery via the buccal route. These innovative polymers provide several advantages, such as adhering longer to the mucosal surface, enhancing penetration through the mucus layer, targeting specific areas, and minimizing enzyme activity. These characteristics make them incredibly valuable for delivering a range of therapeutic agents through the buccal mucosa. Current studies are delving into the use of lectins and “lectinomimetics” to ensure safe and effective drug delivery through this pathway.

Polymers for Colon Targeted Drug Delivery: Polymers are essential in colon-targeted drug delivery systems. They safeguard drugs from being degraded or released prematurely in the stomach and small intestine, ensuring that the medication is released in the proximal colon. For instance, Wong et al. investigated the release of dexamethasone and budesonide from formulations containing guar gum and discovered that drug release significantly increased in simulated colonic fluid when higher concentrations of galactomannanase were present.

A new colon-targeted tablet formulation was developed using pectin as a carrier, with diltiazem hydrochloride and indomethacin as model drugs. In vitro tests indicated that these dosage forms released minimal amounts of the drug in the stomach and small intestine, while most of the drug was released in the colon. Additionally, McLeod et al. synthesized glucocorticoid-dextran conjugates, incorporating dexamethasone and methylprednisolone for enhanced delivery.

Advantages of polymer used in pharmaceutical formulation

- Colloidal drug carrier systems that utilize polymers made of small particles offer significant benefits in drug delivery due to their enhanced drug loading and release capabilities.

- In controlled drug delivery, a polymer (either natural or synthetic) is combined with a drug, facilitating an effective and regulated dosage while preventing overdose.

- Degradable polymers break down into biologically compatible molecules that can be absorbed and eliminated by the body through normal pathways.

- Reservoir-based polymers provide multiple advantages, such as improving the solubility of poorly soluble drugs and minimizing adverse side effects.

- Magneto-optical nanoparticles that are polymer-coated and targeted are detectable by both optical and MRI methods, whereas quantum dots are only detectable optically.

- Some quantum dots contain calcium, which is recognized as toxic to humans. In contrast, polymer-coated or targeted magneto/optical nanoparticles consist of iron oxides/polymers that are considered safe, indicating a promising future.

- Dextran, a common polymer used for coating iron oxide, has been utilized as a plasma expander and has affinity for iron, and it has been employed in treating iron-deficiency anemia since the 1960s, still continuing today.

- In controlled release applications, certain polymers, such as polyurethanes known for elasticity and polysiloxanes valued for insulating properties, are chosen for their specific non-biological physical attributes.

- Modern polymers like poly 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, polyvinyl alcohol, and polyethylene glycol are preferred due to their inert qualities and the absence of leachable impurities.

- Biodegradable polymers are biocompatible, ensuring that no residual dosage remains at any time, while maintaining their properties until the drug is fully depleted.

- In hydrogels used for drug delivery, the characteristics of polymer materials like PEG (a commonly utilized polymer in designing hydrogels) can be adjusted to optimize features like pore size, thereby controlling the diffusion rate of the delivered drugs. PEGylation has been found beneficial for various conditions, including hepatitis B and C, cancer-related neutropenia (PEG-GCSF), and several cancer types [PEG]. Glutaminase was combined with the glutamine anti-metabolite 6-diazo-5-oxo-norleucine (DON).

- Polymers serve a variety of roles, from acting as films or binders in tablet coatings to flow-managing agents in liquids or emulsions, enhancing drug safety and modifying delivery properties. Micelles, due to their smaller size, have a brief circulation time in the body, granting them an advantage in easily penetrating tumor cells through the EPR effect.

Disadvantages of polymer used in pharmaceutical formulation

- It cannot handle very high temperatures because all plastics start melting quickly compared to essence.

- The strength-to-size ratio of polymer is lower, whereas for essence it is higher.

- It is difficult to machine smoothly, and the machining speed is limited.

- The heat capacity of polymer is much lower, making it unsuitable for heat-related applications.

- It is not possible to create heavy structures with polymer because its structural strength is much lower.

- Disposal becomes a problem because some polymers cannot be recycled, while all essence can be reclaimed.

- After being delivered, polymers have a propensity to release a significant amount of medication rapidly.

- From the beginning, polymers exhibit a high degree of drug release.

CONCLUSION

To sum up, the use of polymers has made a big difference in the pharmaceutical industry, starting from ancient times. Polymers have special qualities that make them perfect for many uses in medicine. They are commonly used in everyday medicine forms like tablets and capsules as binders, fillers, dissolving agents, and coatings. These help keep the medicine strong, uniform, and make sure the active ingredients are released at the right time. In special medicine forms that control how fast a drug is released, both types of polymers—those that don’t break down and those that do—are important. They help manage how much drug is released and when, which makes treatment more effective. Polymers are also widely used in medicine packaging because they are flexible, strong, and protect against chemicals and bad weather. Using polymers in the pharmaceutical industry helps make medicines work better, last longer, and be safer. New discoveries in polymer science could lead to even more useful ideas and uses in medicine.

REFERENCES

- Liechty, W. B., Kryscio, D. R., Slaughter, B. V., & Peppas, N. A. (2010). Polymers for drug delivery systems. Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, 1(1), 149–173.

- Saini, N., Bhardwaj, K., & Saini, R. (2024). Synthetic and natural polymers enhancing drug delivery and their treatment: A comprehensive review. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics, 14(10), 153–165.

- Vilar, G., Tulla-Puche, J., & Albericio, F. (2012). Polymers and drug delivery systems. Current Drug Delivery, 9(4), 367–394.

- Singh, B., & Gupta, P. (2016). A review on natural polymers used in pharmaceutical dosage forms. International Journal of Science and Research Methodology, 4(2), 22–29.

- Patil, S., & Sharda, R. (2019). Polymers used in drug delivery system: An overview. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms and Technology, 11(2), 99–104.

- Ahmad, A. (2024). Synthetic and natural polymers enhancing drug delivery and their treatment. Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics, 14(3), 89–94.

- Kaur, R., & Kaur, S. (2019).Pharmaceutical polymers – A review. International Journal of Drug Delivery Technology, 9(1), 1–9.

- Dabir, S., & Shaikh, A. J. (2023). Polymeric drug delivery systems: Chemical design, functionalization, and biomedical applications. Journal of Chemical Review, 5(1), 135–149.

- Heczko, H., et al. (2024).Recent advances in polymers as matrices for drug delivery applications. Polymers, 16(1), 161.

- Tadros, S. (2014). Role of various natural, synthetic, and semi-synthetic polymers on drug release kinetics of losartan potassium oral controlled release tablets. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research, 7(1), 1–10.

- Yadav, M., et al. (2024). Revolutionizing medicine: Advances in polymeric drug delivery systems. International Journal of Drug Development and Technology, 14(1), 1–10.

- Achal Labade, Vikas B. Wamane (2024). A Review on Polymer. International Journal of Novel Research and Development (IJNRD). 9(6), e325-e330.

- Rahul Pal, Prachi Pandey, Arushi, Amit Anand, Archita Saxena, Shiva Kant Thakur, Raj Kumar Malakar, Vikash Kumar (2023). The Pharmaceutical Polymer’s; A Current Status in Drug Delivery: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Survey in Fisheries Sciences. 10 (1), 3682-3692.

- Laxmi Sanjabrao Deshmukh, Damini Anil Mundhare, al (2023). Polymer Used in Pharmaceuticals Formulation. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT), 11(10), e378-e384.

- K. Jesindha Beyatricks, Mrs. Ashwini S. Joshi (2023). A Text Book of Novel Drug Delivery Systems (As Per PCI Regulations). Rivista Nirali Prakashan, Bangalore.

- Shraddha Babasaheb Vyavhare, Khandre Rajeshree Aasaram (2022). A Review on Polymers in Pharmaceutical Drug Delivery System.Giornale Internazionale di Sviluppo e Ricerca Scientifica (IJSDR). 7(12), 158-162.

- Pravin S., Ayyappan T., Vetrichelvan T. Overview on Pharmaceutical Polymers (2021). Giornale Mondiale di Farmacia e Scienze Farmaceutiche. 10 (5), 953-975.

- Devvanshi, N., Yadav, A., Yadav, A., Singh, A., & Mishra, S. (2024). A Review: Polymer and Their Need. Giornale dell’Università di Xidian, 18(6), 1191-1202.

- Sawant, N. B., Tuwar, A. B., & Salve, M. T. (2023). The Brief Review on Pharmaceutical Polymer. Giornale Internazionale di Scienze Umanistiche, Scienze Sociali e Gestione, 3(6), 143-153.