¹ Bioresources Development Centre Odi, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

² Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island Amassoma, Bayelsa State, Nigeria

3 University of Africa, Toru-Orua, Bayelsa State

Corresponding author email: aalifare@gmail.com

Article Publishing History

Received:

Accepted After Revision:

African palm weevil larvae (Oryctes rhinoceros) are widely consumed in the South-South region of Nigeria and valued as a nutritious traditional food. The larvae, naturally distributed across tropical regions, are mostly harvested from the wild. This study investigated the presence and viability of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in the gut microbiota of the larvae as a potential alternative starter culture for yoghurt production. Larvae were aseptically collected from Odi community, dissected, and cultured using the pour plate technique on de Man Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) agar. Incubated cultures were purified by streaking, and isolates were identified microscopically based on cell morphology, catalase reaction, and Analytical Bacterial Identification System (ABIS) Map. The isolate was used to ferment milk, and key indicators such as pH, titratable acidity, and organoleptic properties were assessed.

The LAB isolate from the larvae showed no effective fermentation activity, maintaining a near-neutral pH (6.8), low titratable acidity (72%), fresh-milk odor, and absence of curd formation. In contrast, the standard yoghurt starter culture produced the expected uniform gel structure, characteristic yoghurt aroma, higher titratable acidity (96–120%), and pH 4.5, confirming its functional suitability for yoghurt production. The findings demonstrate that the LAB isolate from Orycete rhinoceros larvae is not appropriate as a yoghurt starter culture due to its inability to meet essential fermentation, safety, and physicochemical requirements. Further research should include molecular identification and screening for functional LAB to determine whether safe, technologically relevant strains exist within the larvae microbiome.

Yoghurt, Lactic acid bacteria, Starter culture, Palm weevil larvae, Orycete rhinoceros, Food safety.

Adediran A, Madukosiri H, Sani H. C. O. M, Afolabi, O. A. Screening And Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria from the Gut of African Palm Weevil (Orycete rhinoceros) Larvae as Starter Culture in Yoghurt Production. International Journal of Biomedical Research Science (IJBRS). 2026;02(1)

Adediran A, Madukosiri H, Sani H. C. O. M, Afolabi, O. A. Screening And Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria from the Gut of African Palm Weevil (Orycete rhinoceros) Larvae as Starter Culture in Yoghurt Production. International Journal of Biomedical Research Science (IJBRS). 2026;02(1). Available from: <a href=”https://shorturl.at/RwMQw“>https://shorturl.at/RwMQw</a>

INTRODUCTION

Yoghurt is a very nutritious food and its continued consumption in the Western World owes much to the development of its health food image (Early, 1998).The methods of production of yoghurt have, in essence, changed little over the years and although there have been some refinements, especially in relation to lactic acid bacteria, that bring about the fermentation. Yoghurt is produced in the form of a highly viscous liquid. Yoghurt is also produced in a drinking form and can be frozen or blended with other ingredients to create, for example, mousse type products, sorbet, yoghurt ice-cream or other forms of dairy dessert (Early, 1998). The initial popularity of yoghurt in Western Europe owed much to the work of the Russian and Metchnikoff, 1908 he attributed the good health and longevity of Balkan peasants to the effects of certain bacteria in the yoghurt they consumed. He postulated the theory that prolongation of life would follow ingestion of a lactic acid bacterium named as Bulgarian bacillus.

The presence of this organism in yoghurt was supposed to inhibit the growth of putrefactive organisms in the intestine. The quality of yoghurt or any food product can be defined against a wide range of criteria including the chemical, physical, microbiological and nutritional characteristics hence food or dairy manufacturers are to ensure that the safety and quality of their product will satisfy the highest expectation of the consumers. The raw material required in the yoghurt production is paramount and as such starter culture is identified to play a key role in a quality and healthy yoghurt processing. As the Nigeria consumer is focusing more towards health and well-being, the volume of yoghurt consumption is steadily increasing. It is therefore of importance that the manufacturer can assure that this food is safe and of consistent high quality.

In yoghurt processing, the lactic acid bacterial have found novel applications in the conversion of fermentable milk sugar into lactic acid resulting in lowered pH of the milk. Isolation of lactic acid producing bacteria will continue to be an important aspect of yoghurt processing industry. Establishing an alternative source of lactic acid bacterial in domesticating Orytce rhinoceros larvae will help to solve one of the problems of food security and job opportunity. This study intends to provide informed recommendation on the use of different local starter culture such as the African palm (Orycete rhinoceros) larvae species in yoghurt production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of Samples: African palm weevil larvae (Orycete rhinoceros) were collected from Odi community, Bayelsa State aseptically into a transparent cover perforated four (4) litres bucket. They were taken to the Biotechnology unit laboratory of University of Africa Toru-Orua for microbiology assessment. Isolates were obtained using standard microbiological techniques and characterized through Gram staining

Isolation and Characterization of isolates: Microorganisms were isolated from the gut of Orycete rhinoceros larvae through desertion, using the pour plate technique and microscopic based on the morphology of the individual cells, catalase test and identified with the Analytical Bacterial Identification System (ABIS) Map

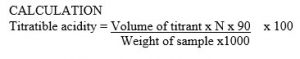

Fermentation: Fresh and powdered milk were pasteurized milk at 820C for 15 minutes, subjected to thermoduric shock to get rid of heat labile bacteria and reduced the temperature of the milk to 450C were inoculated with standard starter culture (yogoumet) and 1ml of the prepared inoculums (0.5ml macfalan standard) of Orycete rhinoceros larvae isolate in fresh milk (ORLIFM) and Orycete rhinoceros larvae isolate in powdered milk (ORLIPM) for eight (8) hours. The pH, texture, odor, color and titratable acidity evaluated by titrating 20ml of the resulting yoghurt containing LAB isolate with 0.1M of NaOH and 1ml of phenolphthalein indicator (0.5% in 50% alcohol). The titratable acidity was calculated as lactic (% w/v), the millilitre of 1M NaOH can be estimated as 90.08mg of lactic acid was calculated in accordance to AOAC, (2000).

Where N=normality of titrant

90= equivalent weight of lactic acid

Statistical Analysis: Data obtained was presented as Mean ± SEM in Tables, Graphs and Charts where appropriate Analysis of variance (ANOVA); and Mean comparism was done using student t-test at 95% confidence level {p=0.05}

RESULT

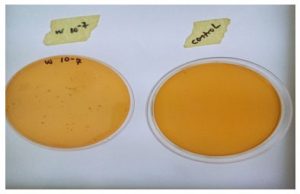

The best growth plate of the homogenized Oryctes rhinoceros larvae gut with 10-7 been the clear separation of the microorganisms as compared to others alongside the control plate. The serial dilution test tube 10-7 shows the best culture plate as shown figure 3.1.

Figure 1: Isolated microorganism from Orycetes rhinoceros.

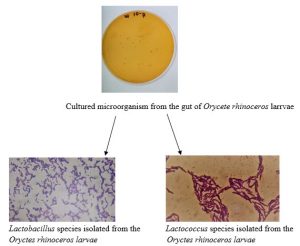

The morphology of the isolate from Orycetes rhinoceros larvae shows Lactobacillus specie two strains of microorganisms with one been rod-like in shape appears single cell and others short chain and second been coccid shape single and short chained Lactococci species as show in figure 3.2. Below.

Figure 2: Two microorganisms isolated were identify as lactobacillus species and lactococcous species.

Table 3.1. Physicochemical Properties of yoghurt cultured with Orycete rhinoceros larvae isolate.

| S/NO | Isolates | pH | Titratible acidity % | Texture | Sensory | Remarks

|

| 1 | Yogournet standard culture on fresh milk (YSCFM) | 4.5 | 96±20.79b | Coagulation formed | Yoghurt aroma | Successful yoghurt |

| 2 | Yogournet standard culture on powdered milk (YSCPM) | 4.6 | 120± 20.79b | Coagulation formed | Yoghurt aroma | Successful yoghurt |

| 3 | Orycete rhinoceros larvae isolate on fresh milk (ORLIFM) | 6.9 | 72± 0.00a | No coagulation | Fresh milk smell | No fermentatiom |

| 4 | Orycete rhinoceros larvae isolate on powdered milk(ORLIPM) | 6.8 | 72± 0.00a | No coagulation | Fresh milk smell | No fermentation |

DISCUSSION

The larvae isolate showed no fermentation capability. These findings contrast sharply with Codex and FAO/WHO requirements. Oryctes rhinoceros larvae contain microorganism that resulted in decreasing the acidity but are not lactic acid bacterial as it did not culture the milk to yoghurt but kept the in its fresh form while the fresh milk and powdered milk cultured with standard culture give the expected codex and FAO/WHO standard of homofermenter.

CONCLUSION

African palm weevil (Orycete rhinoceros) larvae isolates did not qualify as effective starter cultures for yoghurt production. As it fails to meet physicochemical, sensory and antimicrobial standards in yoghurt production.

REFERENCES

- Adedokun, I. I Okorie, S.U Onyeneke, E.N. (2013). Evaluation of yield, sensory and chemical characterization of soft unripened cheese produced with partial incorporation of Bambara milk, Journal of Food Research.1 (1) 014-8

- .Adesokan, I.A. Odetoyinbo, B.B and Olubaniwa, A.O. (2008). Biopreservative act

- Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria on Suya Production from Poultry Meat. Africa Journal Biotechnology, 7(20) 3799-3803.

- Adeduntan, S. A and Bada, F.A. (2004). Socio Economic Importance of Local Silk worm (Anaphe venata) to the Rural Dwellers in Ondo State, Nigeria. Book of Abstracts, 35th Annual Conference Entomology Society Nigeria.7.

- Ademoye, M. A. Lajide, L and Owolabi, B. J. (2018). Phytochemical and antioxidants screening fimbriata. International Journal of Science, volume 7(11) 1-17

- Adeoye, O.T. Adeniran, O.A. Akinyemi, O.D. and Alebiosu, B. I.(2014). Socio Economic Analysis of Forest Edible Insects Species Consumed and its Role in the Livelihood of People in Lagos State. Journal of Food Studies, 3.103-118.

- Adepoju, O. T. and Daboh, O. O. (2013). Biochemical evaluation of the nutritive value of palm weevil larvae (Rynchophorus phoenicis). Annals of Biological Research, 4(3), 214–219.

- AOAC, (2000.) Official Method of Analysis. 17th edition. The Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Washington DC. USA.

- Alexander, M. (1961). Microbiology of cellulose. (2nd Ed.) In: Introduction to Soil Microbiology.Johnwiley and Son Inc. New York. 1 – 50

- Alao, M. S. and Adebisi, A. A. (2022). Agro-waste Capsicum annuum stem: An alternative raw material for lightweight composites. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 18, 4021–4031.

- Alrouechdi, K, (2003). The morphology and life cycle of Red Palm Weevil: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nation: Entity Display:

- Andlar, M. Rezic, T. Marđetko, N. Kracher, D. Ludwig, R. and Santek, B. (2018). Lignocellulose degradation, An overview of fungi and fungal enzymes involved in lignocellulose degradation. Engineering Life Science.18,768-778.

- Alfiler, A. R. R. (1999).Increased attraction of Oryctes rhinoceros aggregation pheromone, ethyl 4-methyloctanoate, with coconut wood. 5.

- Ashiru M. O. (1988). The food value of the larvae of Anaphevenata Butler (Lepidoptera: Notodontidae). Ecology Food Nutrition 23:313-320.

- Aro,N.A. Saloheimo, I. and Pentilla, M. (2001). A Cell, a Novel Transcriptional Activator Involved in Regulation of Cellulose and Xylanase Genes of Trichodermareesei. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276, 24309-24314.

- Asibey-Berko, E. and Taiye, F. A. (1999). Proximate analysis of some underutilized Ghanaian vegetables. Ghana Journal of Science, 39, 91–92.

- Banjo, A. D. Lawal, O. A., and Songonuga, E. A. (2006). The Nutritional Value of Fourteen Species of Edible Insects in Southwestern Nigeria. African Journal of Biotechnology, 5(3), 298–301.

- Bagnara, C. Gaudin, C .and Belaich, J.P. (1987). Physiological Properties of Cellulomonase Fermentans, A Mesophilic Celluloltic Bacterium. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 26, 170-176.

- Bhat, M. K., (2000). Cellulases And Related Enzymes in Biotechnology. Biotechnology Advances, 18, 355-383.

- Belewu, M. A. Belewu, K. Y. (2017). Comparative Physico-Chemical Evaluation of Tigernut Soybean and Coconut Milk Sources. Internal Journal of Agricultural Biology, 9 (5) 785-7.

- Bersford, T. P. (2001). Probiotics and Prebiotics–Progress and Challenges. International Dairy Journal..18, 969-975

- Bluma, A. Ciprovica, I.. Sabovics, M. (2017).The influence of non-starter lactic acid bacteria on swiss-type cheese quality. Agricultural Food, 5, 34–41.

- Bintsis, T. (2018). Lactic Acid Bacteria their applications in foods. Journal Bacteriology Mycology. 6, 89–94.

- Bylund, G. (1995). In: Dairy Processing Handbook, Tetra Pak Processing Systems, A/B, Lund Sweden, 243.

- Banjo, A. D. Lawal, O. A. and Songonuga, E. A. (2006). The nutritional value of four species of edible insects in southwestern Nigeria. African Journal of Biotechnology, 5(3), 298–301.

- Bedford, G. O. (1974). Descriptions of the larvae of some rhinoceros beetles (Col. Scarabaeidae, Dynastinae) associated with coconut palms in New Guinea. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 63(3):445-472.

- Bedford, G. O. (1980). Biology, Ecology and Control of Palm Rhinoceros beetles. Annual Review of Entomology 25: 309-339.

- Bukkens, S. G. F. (1997). The Nutritional Value of Edible Insects. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 36(2–4), 287–319.

- Button, T.A. Rajen, C. (2012). Microorganism in Fermented Foods and Beverages. Asian Journal, 15 (6) 546

- Bylund, G. (1995). In: Dairy Processing Handbook, Tetra Pak Processing Systems, A/B, Lund, Sweden, 243.

- Catley, A. (1969). The coconut rhinoceros beetle Oryctes rhinoceros (L) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Dynastinae. PANS 15(1)18-30.

- Coetzee, K. (2004b). Lacto Data Statistics. The Dairy Mail (Pty) Ltd. P.O. Box 1284, Pretoria. 0001. 11 (3) 115.

- Clover, S. A.(1999). Model Dairy Sheet In: Eeu van NCD / Clover A Century of NCD Clover Roodepoort. 75.(86)

- Crawford, I. O, (2005).Microbial evaluation of yogurt products in Queen City,Egypt.Veterinary World, 6400-06.

- De Foliart, G. R.. (2002). Oceania Australia. In The human use of insects as a food resource: abibliographic account in progress..1-51.

- De Foliart, G.R. (1990). Insects as food in indigenous populations. Ethno-biology Implications and applications. Proceedings of 1st Internation. Conference. Ethno- Biology Belem, 1,145-150.

- De Foliart, G. R. (1992). Insects as human food: Gene De Foliart discusses some nutritional and economic aspects. Crop Protection, 11(5), 395–399.

- Early, R .E. (1998). Technology of Dairy Products, 2nd ed. London: Blackie Academic and Professional, 4,124.

- Ekpo, K. E., and Onigbinde, A. O. (2007). Nutritional potentials of the larva of Rhynchophorus phoenicis. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 6(6), 554–557.

- Ekpo, K. E. (2011). Nutritional and biochemical evaluation of the protein quality of four 3(4), 428–444.

- Ekpo, K. E. (2011). Determination of chemical composition of Rynchophorus phoenicis larvae (African palm weevil). Pakistan Journal of Nutrition, 10(9), 909–911

- FAO, (1983). Eucalyptus for planting.FAO. (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations) Rome, Italy.677, 92-5-100570

- Feller, M., (2020). 8 Reasons greek yoghurt is good for you. Maya Feller Nutrition from https://mayafellernutrition.com/food-facs/we-are-pro-biotics-and-why-people-ready- to-strengthen-their-gut-health-should-be-too/

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations,. (2016). FAO Food Loss and Food Waste. http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en/.

- Fasakin, E. A., Balogun, A. M., and Fagbenro, O. A. (2003). Evaluation of full-fat and defatted housefly maggot meals as a replacement for fish meal in the diets of Clarias gariepinus fingerlings. Aquaculture Research, 34(6), 431–438.

- Fasoranti, J. O. and Ajiboye, D. O. (1993). Some edible insects of Kwara State, Nigeria, American Entomologist, 39 (2): 113–116.

- Farinde, O.F. Obatolu, V.A. and Fasoyiro, S. B. (2008). Use of alternative raw material for yoghurt production. African Journal of Biotechnology.7 (18): 3339-45.

- Fashakin, J. B. Unokiwedi, C. C. (1992). Chemical analysis of warankasi prepared from cow milk partially substituted with melon milk. Nigerian Food Journal. 10:103-10

- Gilmour, A. and Rowe, T. (1990). In: R. K, Robinson, (ed.) Dairy Microbiology-The microbiology of milk. London Elsevier Science Publishers.1,37-75

- Greiner, R. (2006). Biochemical Applications Phytate Degrading Enzymes. Food technology and Biotechnology, 44 125-140

- Gressitt, J. L. (1953). The coconut rhinoceros beetle (Oryctes rhinoceros) with particular reference to the Palau Islands. Bernice Bischop Museum, Bulletin 212.157

- Herbel, S.R Vahjen, W. Wieler, L. H. (2013). Timely Approaches to Identify Probiotic Species of The Genus Lactobacillus. Gut Pathology, 5;27

- Helmenstine A,M, (2007). Is milk an acid or a base? Technology and Math. Thought Company.

- Hansen, E.B. (2002). Commercial bacterial starter cultures for fermented foods of the future, international Journal of Food Microbiology 78, 119-131

- Hinckley, A. D. (1973). Ecology of the coconut rhinoceros beetle, Oryctes rhinoceros Coleoptera: Dynastidae). Biotropica 5(2): 111-116.

- Johansen, E. (2018) Use of Natural Selection and Evolution to Develop New Starter Cultures for Fermented Foods. Annual Revised Food Science Technology, 9, 411-428

- Karmakar, M. and Ray, R. (2011). Current trends in research and application of microbial cellulases. Research Journal of microbiology, 6 (1), 41-53

- Kamarudin, K. M. Wahid, B. and Moslim. R. (2005). Environmental factors affecting the population density of Oryctes rhinoceros in a zero-burn oil palm replant. Journal of Oil Palm Research 17:53-63.